Lionel Kalish

The Lark: A Conversation With Lionel Kalish

The exclusive interview with the man behind 30 years of illustrations that permeated popular culture from the late 50’s into the 80’s.

written by

Francis Rourke

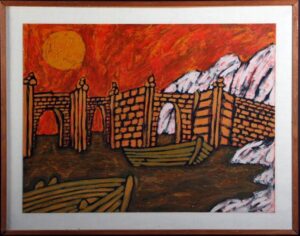

Lionel Kalish is an artist who worked as an illustrator for many ad agencies on Madison Avenue during the “Golden Age” of advertising. He later founded his own agency with his wife [Muriel Kalish] and then with his rep [Cullen Rapp], before putting his pencil down for good and picking up a paintbrush to explore the Italian landscapes of his own imagination.

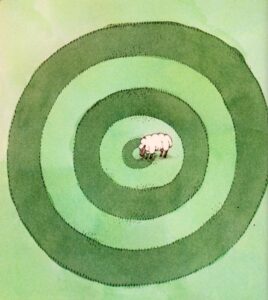

During his some thirty years as an illustrator, Kalish produced work for record covers and picture book publications such as Parents Magazine Press and Quist Books, including The Cat and the Fiddler, The Sheep of Lal Bagh, and A Children’s Garden of Verses.

Kalish also contributed illustrations to the illustrious magazines Eros, Avant Garde and Facts, created by Ralph Ginsberg and Herb Lubalin, and was commissioned to illustrate a cover for LIFE magazine’s Summer Nomads issue in 1970.

A CONVERSATION WITH LIONEL KALISH, THE PAINTER

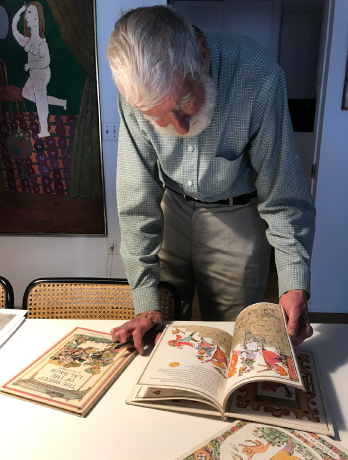

The man before me, grey in hair and face with eyes the color of hazy smoke. He is a tall, lean man. When he speaks his words are carefully measured, weighing the intention and affect of how and what is being said— This a brief insight into the artist’s life. His past and his present. This is the artist.

Rourke: Let’s talk about how you got started. You went to school for illustration, but not for painting, right?

Sort of. Not exactly the way you put it. It doesn’t exactly work that way. But I’ll tell you about the schooling too— At least my take on the schooling— It’s subjective.

There was a high school — Well known in New York. It’s still there but it has a different name — It was called Music and Art. And the kids there were very accomplished musicians— that was the music. And you had various strenuous tests you had to take to get in. I was fourteen then. So I went to that high school — Music and Art — After that I went to another school called Cooper Union. It’s kind of a landmark in this town. And that was strictly for art. And so I had about seven years of art schooling. And I sort of studied art, but not really.

See, I was in love with cartooning. When I was a kid I fell in love with cartooning. I began drawing full-time when I was about four years old. I grew up in the Bronx. My parent’s were both Jewish immigrants from Poland and they worked in what was called the Garment Center. It was a well-known kind of deal in this town. They were sweatshops. And they didn’t really know or understand art. They felt that art was a misguided pathway for anybody because you’d never make any money. And it was silly— And I would lie down— I worked on the floor— So for all those years in that apartment I worked lying down on the floor. Don’t ask me why. And I would be drawing the whole goddamn time. I sometimes copied the comic books, whatever they were. I also thought “I want to do that. I can do that in my own way.” I always felt that even as a little kid. I could look at a cartoon and I’d think “I can do that and I’m gonna do it my way.”

I was even in love with the word ‘cartoon’. There was a magazine in those days, and in the back they’d have these ads and on these ads they’d say “learn cartooning” and I’d see that ad and the word cartooning and the hair would start standing up on the back of my neck. That’s how connected I was. So I thought of myself— without realizing it— I’m a cartoonist. I never had to wonder what I was going to be in life. Some kids think I’ll be a fireman or an astronaut. It wasn’t that way with me. I never said it, but I knew this was me. That was it from here on in.

“I think I was fired from jobs more times, more often, then any other kid out of school.”

The schooling I had— The high school and even Cooper Union— They didn’t really teach you anything. Not really. They had a set of theories that didn’t take hold. I wasn’t interested. They didn’t really care. By ‘they’ I mean the teachers. Most art teachers, especially at Cooper Union, were professional painters. All they cared about was their own work. I don’t blame them. That’s how I am. And these kids were an impediment. ‘Why am I stuck here? Well I need the money. If only I could do my own work and not bother with them.’ So they didn’t really teach you anything. They had a set of principles in a way but they didn’t fit me. All I wanted to do was cartoons. I had no notion of painting. I didn’t understand what painting was about or why is was supposed to be worthwhile. And that was until I was about 21.

I graduated, then I got various jobs— (Chuckles) I should tell you this. I had a very unusual first year. But it shows well for me. I’m proud of myself. I think I was fired from jobs more times, more often, then any other kid out of school. Maybe even forever. And I can compete. Because I didn’t know anything. I tried to get jobs in advertising. Well I did get jobs in advertising right after school. You did get jobs. (Chuckles) I’ll give you the whole dope— I faked up what they call a portfolio. You had to have a portfolio. And I didn’t have any experience so where am I going to get a portfolio. It had to look professional. So I made up ads. I pretended they existed. And I got them copied in someway— I don’t remember how— that was before the age of xeroxes— But I did them and they looked authentic, really. And in that way I got jobs. But I didn’t know anything. They didn’t teach me anything about how to do that sort of work.

Rourke: How did you learn the sort of tasks necessary for that work?

There was what you’d call ‘paste-ups’— Because you pasted your work— And you had to know how to do that and how to do it quickly. I didn’t know anything— So in the first year of my out-of-school life, I was fired at least twenty times. I’d often be fired by lunchtime. I’d go there and by noon they’d say ‘No you’re not going to work out’ and I never told my parents because they would’ve been very upset so I’d always pretend to be going to work even though I had no work for at least half the time.

In those days there were employment agencies. So you could get a lot of jobs. Hiring was easy. If you showed the portfolio they sent you somewhere and they’d say ‘Ok we’ll take you on’ until they discovered very quickly that I didn’t know how to do anything. So that was the end of that. But I persevered. That was how I learned how to work in advertising. The schooling was nothing. The little bit I gleaned in the few hours they permitted me to be there I learned enough to kind of begin to get by and I did work in advertising agencies doing various thing just to make a living for about seven years or so. But I was always cartooning and drawing at home. All I cared about was cartooning. And eventually I got what was called a rep. This was before I met [Muriel]. I showed them my work. That I could do because I was already an accomplished cartoonist because I had been doing it so long and so constantly. I began to get work. Then we met (Speaking of Muriel) and we married, and Muriel wanted to be a rep. So we joined forces. I became quite successful pretty fast. And that was in my working life as an artist. I’d call that my ‘Golden Age’.

An other thing is— It’s weird about Madison Avenue— You know, it has a bad reputation. But I found the people we dealt with then were much nicer much more supportive, much more appreciative. Honest. We were on the same wave length. They kind of knew what they were doing. You know, believe it or not, a lot of art dealers really have no idea what they’re doing. And we were lucky. We were young. We were a team. We were the perfect team. I wanted to be left alone. I still do. Completely. So I’d be home alone. I don’t want to see anybody. I don’t want to talk to anybody. I just did the work. Muriel is great at talking to people. And meeting them. And everybody liked her. And she got the work because she was the rep.

Rourke: How old were you at that time?

I was about twenty-three or twenty-four to about the time of my early thirties. Those were those years. They were our most successful years. I was made much of. I made a real hit. I got a lot of work. I was complemented the whole time. I was doing what I really— See it’s funny. I was not born to be a painter. The work I just showed you is not my natural work. I struggled with this. I do my very best. I work hard. I get there by applying myself no end. When it came to cartooning it was like breathing. It was so easy for me. I never struggled with anything. I could do anything in that realm. No problem. And I did. And I was highly successful. That was our ‘Golden Age’.

Then I began to have doubts. A little like losing your faith if you’re religious. Doubts began to creep in. And the doubts were basically of one kind. I’m thinking ‘Wait a minute I have my feelings. I’m an artist. I want to do my art. And I’ve been doing it, but there’s a problem, I never do what I’m interested in, ever.’ In other words, someone like me, as an illustrator, I’m a tool. I’m like a hammer. Like a screwdriver. Somebody wants something realized, a drawing of some kind, a piece of art, and they have the idea but they can’t do it. But it’s their concept. They call somebody like me and I can do it. And I bring their thinking to life. But I never realize any of my own thinking. I never conceive anything. And slowly that began to eat away at me. And I began to think this is not the life of an artist. This won’t work. I can’t do this for a lifetime. And that’s when I discovered painting.

I came in at the backdoor. Because I had never been interested in it. Never thought about it. I had never known of it. It dawned on my very slowly, very slowly, ‘Well wait a minute, painters get their own conceptions.’ They try to realize what they— And I still do today, I’m trying to realize what my innards tell me— I don’t know why they tell me this— But they’re my innards. They’re a part of my being. They’re what I’m about. They swim up to my consciousness and say you ought to do this. But now I’m doing what I believe— Who I am you could call it— Who I truly am. I’m no longer a tool. I’m my own, you know?— That has been both very satisfying and had its dark side as well.

And I was also not born to do this. I do it by dint of very heavy weight application. I do well. I think I do good work. But by dint of very heavy weight application. And that’s what I’ve been doing. I never regretted it because basically the basics are as they should be. You are now working on what you believe and who you are. That’s good. So I’ve never regretted it. But it’s been a bit of a rough ride in various ways. Also the art world is much harder on you than the world of illustration if you’re good. That world was very welcoming.

“It was just like a marriage, a bad marriage, but it was a great marriage— What I had loved with all my heart I began to truly hate.”

Rourke: Do you have a routine? A way you go about the day?

The way it works for me is I get ideas. I’m really lucky. I get a lot of ideas. I put them in file folders and I’ve got a million file folders. I always have a lot of ideas I haven’t gotten to yet. But where they come from and why I get them I don’t know. It’s a mystery. But they do come into my head. And then I want to do that. And when I get the idea I feel ‘This is going to be good. This is really going to be very good.’ Always before I start. Sometimes, yes. Sometimes, no. But I do them because they came to me and this feels like what I want. It’s a lot feeling. It’s instinct.

Rourke: So you don’t have a way of going about it, you don’t get up in the morning and go to work?

No, but I always feel like working. I always feel I could do some work if only they’d let me alone. Some good work. So I always feel like working that’s the problem between us sometimes (Speaking about Muriel) She feels I over do it a bit. But you are who you are. You don’t have to understand it.

Rourke: You were telling me you went through a dark age, how doubts began to creep in?

Yes, when I made the transformation from illustrator to painter. So how that went— I began to hate [illustration]. What I had loved— It was just like a marriage a bad marriage, but it was a great marriage— What I had loved with all my heart I began to truly hate. I couldn’t stand getting the assignments and getting the work and I was now painting the whole time. So I always felt the illustration was in the way of my— ‘My work’, I began to call it my work, my painting. ‘This is my work and illustration is getting in the way of my work.’ I needed it. I’m very lucky the way I became a painter. I don’t probably have enough strength in a way— Well, let me go back to my parents.

They were very poor and they were immigrants, they didn’t fit in that well. And they worked on garments, and they had a great innate feeling about money and I think I was left with that. You had to earn enough money. It was in the air. Somehow it was pervasive. You had to earn enough money in this life. And I hated the work but I was making good money and I didn’t have the strength to get rid of something voluntarily that brought in good money, because a part of my legacy was this feeling about money and how it was so emotionally weighty— It was for my parents, god knows— So I couldn’t leave it. I just got lucky. It left me. I was busy busy busy busy and I ended up with one big account I got to work for. It was the Armed Services. And for some reason— I never knew this— the telephone company wanted to influence the Armed Service— Don’t ask me why— They wanted them to make a lot of phone calls (chuckles). So the Navy, the Army, the Marines, the Air Force— there was an advertising agency that worked for the phone company and targeted solely at the service. And I was their illustrator. I was busy as hell. Making a lot of money and in the end, I didn’t even realize it because I was painting.

I didn’t want to realize it. I didn’t care. Let me do it. Let me get rid of it. What the hell. But they were my only account. I was dimly aware of that but I didn’t care. I was painting as much as I could. They were in the way of my painting. Or ‘my work’ as I called it. So one day I got a phone call from my rep— Not Muriel— I had another rep at the time— So one day I got a call from my rep, and he said, ‘You know they called me and they want to take a different direction.’ So believe it or not, it was just like a bad marriage only you’re the one that’s dumped. And you get angry. And you get unhappy. And that’s exactly what I did. I didn’t want it, you know, in the upper reaches of my conscious, but somewhere in me ‘They can’t get away with this!’

Rourke: They affected your ego?

Very silly, but very powerful. So I said to my rep, ‘Ok.’— I had no more work at that time. They were my only account— ‘What I’m going to do is do a completely new style and it’ll get work.’ And I worked on it. I worked hard. I tiddled around. I experimented. I was really putting my mind to it. Why? I don’t know. Because I really shouldn’t have. Worst thing in the world for me. I was down the day I got that call. But it was the greatest call of my life. But who knew it at the time. So I did that and I showed my rep my samples and he said, ‘This is going to work. This is going to get you a lot of work. This is great!’ But it never did. I never got a call to do a job from that day to now. That was about forty years ago.

I had a thought. You know, I am told by some— ‘You’re an artist and you must love your work.’ That’s not really true for me. I have a wide range of feeling toward my work. I do love it sometimes. I hate it sometimes, too. And there’s all the grey in-between. I’ll tolerate it— The one thing I do feel though that I hope you feel this way about your writing is that this is what I was put here to do. This is just right for me. I may hate it today, but I know I’m doing exactly what I ought to be doing with my life. That’s what truly sustains me. Because making art is daunting. And it often goes wrong. And it’s both dark and light. When its going well you’re feeling good. When its not going well you’re oppressed. It’s a heavy weight feeling. I always want to be doing my very very best and I feel that I did. But you’re human and it doesn’t always work that way.

So I’ve done a lot of drawings recently. They’re pencil drawings and they’re much larger than most drawings tend to be.

Rourke: Do you feel that drawing on a larger surface affords you more breathing room to capture the finer details?

See, I feel that art is a little bit of a mystery— well, let me tell you a little about how I am— I want to make art. I feel that in every generation there is a small sliver of the population who wants to make art. We’re actually two of them. You want to make your kind. I want to make my kind. So if you ask me why do I do this, I would say because I like to do it and I want to do it. But if you were to then say “Well why do you like to do it and want to do it?” I have no idea. None. All I know is that when I was a kid— a little child— I began— all children draw. I never stopped, because I had some sort of impulse which I don’t really understand— to make images. I’ve always needed to do that. And there are a small group of us in every generation that want— who need to do that. And so they do it. Why? I don’t know. Why I work this size? I don’t know. All I know is there is an impulse that says that’s what I want to do. And I don’t really question it. I think of myself as having a little man— but you can look at it any way you’d like— an inner voice that tells me what I ought to do and I listen. And when I don’t I pay the price. I’ve learned to listen. But why it says that or what it’s all about I do not know. Not really. I just know I want to and need to.

“…and I’m thinking, it’s dark and I don’t know this place, why did we do this? Why in the world would we have done this? And I think I had actual tears in my eyes at this horrible mistake that we had made.”

Rourke: You tend to use a lot of thresholds in your work. Is there a reason you do that?

Yes. Windows are an enhancer. Absolutely. They enhance things just naturally. And there’s some range to them. They vary. I like range. I’m also very interested in walls and surfaces. Very interested—This is typical of Italy. The surface itself is beautiful—Artists are also kind of collectors, I feel. In other words, you see something and you think I want to have that. I’m going to make it. And then in a sense I have it. I own it. And I don’t even want to understand it. I feel. Let me put it this way, I feel I was given, even though I don’t like it some of the time, I was given a great gift. It came from nowhere. There was no art in my home, in my childhood. I don’t know why me. I’ve been an artist all my life. In other words when I was in grammar school I drew all the time, the other kids would say ‘Oh you’re an artist. That’s great. Blah blah blah.’ I don’t know why or where that came from but I was given it. I’m now eighty-eight and I’m still doing it every day and I still want to do it and I feel that’s a tremendous gift I was given.

Rourke: Do you feel it’s a gift you were given to share with others?

To tell you the truth, I don’t really work too much for the viewer. I want to do it. Let it fall where it may. I’m really kind of working for myself— And by the way I don’t really understand other people anyway. I don’t even understand myself, let alone other people. So I couldn’t do it if I wanted to. I don’t even get myself so, yea, I really only work for myself— And again, Italy. I fell in love with Italy the first time I went there. Our first trip. And I thought ‘That’s what I’m going to work on. That’s so beautiful. Look at that. I gotta do it. I gotta have that.’

Rourke: Why do you paint Italy?

We went to Italy a lot— Once I fell in love with Italy— We went back and kind of been around the whole place in a way. Venice. Venice especially— I’ll tell you something about Venice. As a tourist there are three or four places that are terrific but they’re very very crowded. It’s a very small town. Very small. You see it from the air you can’t believe how small it is—The Piazza San Marco— The Realto— There are about four places that are very very crowded. The tourists go there and somehow stay there but if you leave those four and walk around Venice— It’s easy to do— You almost never see a tourist. Every corner is beautiful. Everytime you turn a street it’s another great thing you didn’t expect. It’s an unbelievably fantastic town. My work isn’t exactly, but it’s based on Venice. Nothing in my work is exactly.

We wanted to— Well, I wanted to be an expatriate. Our daughter was about twelve. And think ‘I’m going to be an expatriate.’ And Muriel went along with me, it was very good of her. ‘So what we’ll do is I’m a busy illustrator, we’ll take the samples over to— we’re going to start with London because they speak English.

Rourke: Was that to get your way in and work your way down to Italy?

Yes. ‘We’ll live in Rome and we’ll get busy. I’m going to start in London. We’re going to find reps’— there were plenty of reps in London. We had a list of them for commercial— You know, illustration. And I was good and all that. And so we went to London and we saw a lot of reps with my portfolio and they said, ‘Look you’re good and we’ll rep you, but you got to be in London. We’re not going to rep you in Rome.’ It was way before the technology age and you couldn’t do it then, it was too cumbersome. Today you could’ve gotten away with it.

So I said to these guys, ‘No, I don’t want to be in London. The point is I want to be in Rome.’ So then we went to Rome and we saw a rep or two but there was nothing like that in Rome. Rome is actually a very provincial city in real life. Venice is even more but it doesn’t matter because it’s so beautiful. And so there was no work for me in Rome, so we lived in Rome for about three months because we were casing it out. It was a great three months.

Turned out we couldn’t really work. That was the end of my expatriate dream. But I’ll tell you something interesting about living in Rome, we went to Rome to live. We got a nice apartment in a very good area of Rome. Really very good. Just where you should be. And we’re in Rome and it’s night—the first night in Rome, and I’m thinking, it’s dark and I don’t know this place, why did we do this? Why in the world would we have done this? And I think I had actual tears in my eyes at this horrible mistake that we had made. You know, we’re in the middle of something god knows what this is and it’s night out there. I don’t know anything. We lived there for three months and I think it was the best three months of my life. So it shows you how very very wrong your emotions can take you. It was great. We loved every minute of it.

Rourke: You worked in Rome?

Oh a lot work. We do as much work as we can wherever we are. If we can. I’m a fanatic when it comes to work. Emotionally if I’m not getting my work done I feel down. I feel that something is badly not working.

Rourke: So you were in Italy and thought you had made a huge mistake?

No, that worked out great. It was a great idea but we couldn’t work there so we came back and then I had the feeling I had to change this thing. And I became a painter through the backdoor as I told you. And painting was a great struggle for me. I wasn’t used to struggling with anything related to art because cartooning I hadn’t even realized I was learning it. I had done it so long and it was so right for me. Now I was faced with something I could not do and I didn’t know what it was all about. And it was foreign to me in a big way. So I had a rough five or six years when I didn’t know what to paint. I tried everything in the world I could think of. I was floundering. I was flailing. Silly stupid work.

Rourke: Some of the paintings, I imagine that were of this time, or maybe not, maybe they were a progression coming out of illustration and advertising, were some oil paintings I’ve seen of boats near a village. One I think was called One Master?

Who remembers the titles.

Rourke: There was another one with lions in it?

Lions? That sounds like my early work. Yea, that was flailing.

Rourke: That was flailing?

Oh yea. Terrible. It was terrible work and it felt terrible at the time. But again, see, I guess I have— I think if you’re an artist, if you’re a writer too, you better have a kind of iron will. That goes for you too, I think. So I guess I do have it, because my first year out of school was very damaging emotionally. But I pushed through it. I survived.

My first four or five years as a painter were again very damaging because I felt instinct and I was right. I wasn’t fooling myself. And you’re not finding it, you’re not getting anywhere. And I had enough will to keep going. There was no way I was going to quit. I don’t know why. I just felt that. And then I discovered Italy. And in a very short time I began doing that. And after that I was on a kind of good ride and improving the whole time. Because I feel I’m still improving at eighty-eight. I feel like what I showed you is some of the best work I’ve ever done. I’m very lucky in that way. You could very easily be a has-been at eighty-eight. Or retired or whatever. I’m only going to stop when I physically can’t do it anymore.

“But if the day came when I genuinely didn’t want to do it— I don’t think that’s going to happen. It never did— I would dump it.”

Rourke: Is that because you find the process appealing?

It’s not that I find it appealing so much. Because some days it’s not appealing. It’s that I find the work a center for me. It’s who I am. It’s what I should be doing. I’m interested in it like crazy. I get up in the morning and think, “Let me see how this is going to go.” And every time I start a piece I think, “Can I do this?” I don’t know. We’ll find out. Let’s see. So that’s how I feel about it. So I’m never going to stop. I pushed through that dark— But you have the modeling, that was my dark ages and I began painting and then I got galleries. I connected with galleries. Galleries are often very difficult. They’re not good to work with.

Rourke: Your work has been shown all over the country and in Europe as well?

Yes. I’ve been in a lot of galleries— You know— I read somewhere, I think, some psychologist had a patient who was complaining about not being able to do— to try his best his whole time in his work and it was a failure. And the psychologist said “Don’t worry about it. Nobody tries their best the whole time it just isn’t the human way.” But that pissed me off, because I try my best the whole time. Every split second I’m working I’m putting my whole heart and soul into it. It doesn’t always work out but not through lack of effort. I’m focused. I’m highly, highly involved and doing my best every split second.

Rourke: At what point do you feel you have to walk away when something isn’t working out?

Well I mainly fix things. I seldom walk away. There are a few days I feel I can’t face this, I’m not going to do it. But that’s rare for me. I work just about everyday unless we have to do something or go somewhere. Even if it’s not going well then I’m fixing it. I feel, “I can fix this and I better fix it.” . . . You know one thing about painting, we both suffer from it [Talking about Muriel]. Painting is very deceptive.

Rourke: How so?

It’s a little like being anorexic. It really is.

Rourke: Why do you say that?

An anorexic looks in the mirror and sees someone who is seventy-pounds and thinks, ‘Look at me, I’m like two hundred and fifty pounds here.’

Rourke: I’m a pig.

Yea. Look at me. I’m a pig— That’s painting. You look at what you’ve just done— This is typical, this happens to me all the time, and Muriel too— You look at what you’ve just done and think, ‘Boy, I’m good. Look at this. This is really— I did a good days work. This is really good.’ You put it away. Let’s say you don’t see it for three or four days, then you go back to the wall, ‘What the hell did I do here? What’s wrong with me?’— That’s the common experience. But then I feel I’m going to fix it. And by god I’m going to fix it. It’s par for the course. It doesn’t phase me too much because it’s happened so very often— We use devices. We look at it through a mirror. That shows you things. You put it face to the wall. That’s the best one then look at it three days later.

Rourke: When looking at your earlier work to your present work there’s still a quality of you in them.

Well naturally. That’s true of every artist. You know, one thing about art and I think it’s definitely true of writing, too— That’s also art— You can’t really hide it. Who you are will out. There’s no question about it. You like it. You don’t want to. You do want to. It’s going to happen. Who you are will definitely show up.

Rourke: Are you influenced by any early painters? Do you feel that you— not emulate, but are inspired by earlier works?

Oh yea. You can’t emulate them. See that’s another things about painting. I feel I’m good that way. I don’t— Let me put it this way, I feel— I don’t know that many painters. We know some. But I feel that many painters feel that they’re great. I’m not great and it doesn’t bother me. I’m me. What I want is to do the best Lionel can get out of himself. I don’t have to be great . . . So for instance there’s a painter called— you may be familiar with him, called Hans Holbein.

Rourke: I’m not familiar with him.

The Younger. You would like his work. You should look him up. Hans Holbein, The Younger. So I consider him the best painter that ever lived. And I’m very influenced by him. He doesn’t do what I do. In other words, if you’re a painter I feel you should be yourself. That’s the whole point. So I would never try to— Luckily— try to emulate someone else, or work as they do or feel. That would be counter to the whole thing.

Rourke: I saw in your earlier paintings— the work we spoke of— there was a slight sense of the Impressionists in them.

That’s because I didn’t know what I was doing. I was used to solving things. That was my whole working life. Somebody sends you a thing, you solve it. So I took that approach, I guess. Maybe Impressionism. Maybe it was broad strokes. Maybe. I didn’t know what I was doing. I was trying anything and everything. It was a rough time. Not good. Much better to have a strong feeling about what you’re doing. I hope you feel that way about what you’re writing. There’s one thing about fiction that I feel— I don’t know if anyone else feels this way— To me fiction is schooling, to the reader not the writer— Schooling— It gives you a much deeper insight than non-fiction does into human affairs, human behavior, human psychology. It gets much deeper. It gets below the surface. And tells you what underlies things. I feel I know a lot more about human— I’m interested in human affairs by the way. And I feel I know much more about human affairs because I’ve read a fair amount of fiction and they’ve been my teaching.

Rourke: Do you paint from memory? Or do you take photos?

I will have some photos of a building here and a building there, but I— No. I make them up. I get images and then I create and follow them. There sort of a pseudo-Venice. It isn’t really.

Rourke: That’s kind of the beauty of it. You get to create your own world.

Yea. Exactly. That’s what I’m after. I value a certain kind of freedom. Where I’m not stuck with anything that is. I want to go my way.

Rourke: You said The Sheep of Lal Bagh was your best children’s book. Was that because you got to create the world in it?

No, it was because I was able to step into a sort of exotic world. Which was a treat for me. I did some research and loved the visualness of it: how people dressed and what they looked like in that era. And I felt I was able to stretch out and do my best work. The story adapted to that. It just work.

I actually never even met the guy who wrote it— Speaking of the past— I don’t really remember things— I’ve got a poor memory, generally. But let me tell you one thing about artists— I think, generally. And it’s certainly true of me. The way it works for me and I think most artists— Most visual artists— is the one I’m doing. In other words, my entire innards and soul is focused on the one I’m doing. That’s the one that counts. What I have done in the past means practically nothing.

Rourke: It’s surprising to me that people are buying your art in Texas and around the world and they’re not even curious about the artist.

I’ve been at it forever. And so has Muriel. I have met one— we became friendly with one couple in Texas who buys my work. But I’ve never met a collector— I’ve sold a fair amount of work in my life— Never met a collector who liked my work well enough to buy it. Nobody was ever interested. Not even one— Well one, but one only . . . That surprises me too.

Rourke: Yea, that’s strange. So they just buy the work and that’s it? No curiosity whatsoever?

Yea, it’s strange to me too. In fact, I’d say in a long long life, this is it. This is it. You’re the first human who has ever shown real interest, that I can remember— You know, I have a theory— It’s not a theory— A principle— whatever you want to call it. I do this work that I do because I want to do it. But if the day came when I genuinely didn’t want to do it— I don’t think that’s going to happen. It never did— I would dump it. I don’t think it makes sense if I’m forcing myself or kidding myself. I feel the impulse genuinely has to be there. Otherwise it wouldn’t bother me. That’s the end of that. I guess it would bother me but I would do it anyway. I wouldn’t keep going for some artificial concept.

Rourke: I don’t think people understand how much time and effort you put into those illustrations and then having to come out of it like you did to become a painter. See, what’s strange is you did all this ad work for years and what you’re mainly known for on the internet is your children’s book illustrations.

At least I’m known for something— But that isn’t the key thing anyway. That sounds so high flown in pollyannics, but it happens to be absolutely true. You better be working for yourself in this thing or get out of it. I mean it. No two ways about it. It just happens to be the truth. I can’t help it.

Rourke: That’s bizarre to me that nobody thought to talk to you about why you’re doing what you’re doing.

You know this is going to sound noble or artsy or something, but it doesn’t really matter. I’m going to do it. That’s it. How it goes outside— I like it. But it doesn’t really matter. I’ve got to do it. I’m going to do it. By the way, I’m kinda self-taught.

Rourke: You do have followers out there, though. People are aware of your work.

Two guys in Belgium and one in France.

Rourke: Do you not want to talk to the Belgians?

Ah what the hell. It’s touching in a way and I appreciate it in a sense. One guy actually said, ‘I studied’— I’ve never taught a day in my life by the way. I was lucky I didn’t have to. I was successful enough. But one guy said—is on record saying, ‘I studied with him for years and was a great inspiration.’ Meaning me. I never taught a day in my life. In a way I’m very divorced from it. But in a way I got to admit you do have an ego— We’re all human— Even me— and you’re pleased by it in a certain way when people think highly of you.

Rourke: You mentioned earlier that you mostly want to be left alone to your work. I wanted to let you know I appreciate you taking the time to see me.

I think of this as kind of a lark. No one else ever interviewed me or showed interest in my work. I’m eighty-eight and never in my life has anyone ever wanted to interview me, but you. That’s why I accepted yours. No one has ever wanted to hear me speak about what I do. Never.

For any inquires on how to purchase Lionel Kalish’s work contact Gremillion & Co. by clicking their image below.

Letters From San Tropez, CA

A collection of writings from Rourke’s private Riviera, what some have deemed the “unwashed colon of California”.

In this book is the three-part story where Rourke discovered Lionel Kalish’s work, took a red-eye flight to New York, and sat down with the artist himself.

Also included in this work is a short story about an idealistic nihilist who denounces his own acolytes, an old man who takes Time in his own hands, and an essay examining the current state of Steinbeck country, and much much more.

Purchase it HERE.